When it comes to long running gaming franchises considered gaming royalty, it’s hard to deny the power and impact of Nintendo’s The Legend of Zelda franchise. When a new entry launches, everyone stops and pays attention. This is especially so when an entry in the series sets new standards that many developers emulate and build upon for years down the line. It happened with the original and its SNES sequel The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past, it happened with 3D gaming with The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, and, if you ask many people, it happened with 2017’s The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild.

It’s hard to understate the impact Breath of the Wild had on the industry when it launched as the Nintendo Switch’s opening salvo. Here was Nintendo with their first ever open world game re-imagining the franchise after their last game The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword failed to resonate. Harkening back to the open design of the original NES game and realizing its open philosophy in a 3D environment, many point to this game as the one that brought back adventure, authorship, and true discovery back to open world games compared to other popular entries in the format. When you see a game like last year’s Elden Ring take these design tenets and make them work in their own game, along with many other developers slowly embracing these tenets, it can be hard to deny Breath of the Wild did something right. And with 29.81 million sales lifetime in the bank, it is clear that many players feel the same.

Just to be transparent, as a big Zelda fan who considered the run from Ocarina of Time to Twilight Princess my favorite era, I liked Breath of the Wild but never saw in it what others did to declare it “the greatest game of all time.” I give it its props for what it did with open world exploration as I can’t deny that I spent countless hours scouring the map, loving how organic it felt. As a longtime Zelda fan, I felt that what it did for open worlds came at the expense of the things I liked about Zelda. I didn’t like how any sense of story fell to the wayside. The survival elements felt like annoying busywork that worked against your enjoyment. The weapon durability was comical. The lack of true dungeons was a bummer.

What it did great, it did excellently. But all those issues I had combined together to make it far from my favorite Zelda game. Seeing the unanimous praise the game continued to get in lieu of my issues always confused me.

I definitely came into the sequel, The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom, both with interest as a longtime fan as well as some trepidation. As the first direct sequel to a Zelda entry since 2000’s Majora’s Mask, I wanted to see how Nintendo would follow up their critical smash hit. Would they double down and expand on everything they did with the last one? Would they be willing to make the things that fell to the wayside things that could work with the new formula?

130 hours later, the answer to both questions is a resounding YES. Tears of the Kingdom manages to be an even more expansive game than the last one. It finds ways to make what felt like annoyances feel more fleshed out to create a more satisfying gameplay loop. It brings back elements from older games and makes them work in the context of the new format. And it manages to make the last game feel like a first draft tech demo, all while delivering a game with such unfathomable scale and polish, it’s insane it was possible on Nintendo’s decrepit decade-old hardware.

A Gloom of Twilight

Picking up sometime after Breath of the Wild, Tears of the Kingdom opens as both Princess Zelda and Link explore the hidden catacombs of Hyrule Castle to find the source of an unknown substance (which we learn is called “Gloom”) that’s been causing illnesses across Hyrule since the defeat of Calamity Ganon. While in the ruins, Link and Zelda find some ancient civilization inscriptions detailing the war against the Demon King, and they later come upon a mysterious, desecrated body. After Zelda and Link mistakenly awaken this evil figure from a millenia-long slumber, all hell breaks loose as he unleashes the Gloom across Hyrule in what is known as “the Upheaval.” Link becomes the new Anakin Skywalker and loses his right arm to the gloom, and Zelda falls into a chasm before disappearing in a cloud of light while Link is whisked away to the skies by the glowing arm that was holding the awakened figure.

Compared to the beginning of Breath of the Wild where Link wakes up and is immediately sent into the world, the beginning of Tears of the Kingdom does a much better job at establishing a story backbone, and the stakes of this story from the jump, even when it seems like a typical story of “you are Link and need to rescue Zelda.” Compared to the last game, Tears of the Kingdom definitely spends more time introducing its initial story elements, explaining why we suddenly are going to be venturing through different islands in the sky. It also provides some interesting “origin stories” to the world of Hyrule, giving the impression of another attempt by Nintendo at an origin story after the tepid reception to 2011’s Skyward Sword (a game that, for my money, found its strongest element being its story, but I digress).

To Nintendo’s credit, on top of the new elements, they play around with the Zelda tropes in a more clever way than you would expect, and, for once, give Princess Zelda way more agency in the story, subverting the usual “princess you have to find and rescue” trope. The reveal of where Zelda went after disappearing at the beginning of the game, her adventures in said place, and her current whereabouts are some of the game’s strongest story moments.

If there is something that can be slightly disappointing about the way this game tells its much improved story, it is the fact that, similar to the last game, most of the story elements are hidden behind a quest to find things in the world instead of just linearly getting all these story moments just by following a mainline path. But on the flipside, the way you find these story moments are way easier to catch as they are blatantly visible in the world. If you actually follow a main questline that the game signposts you toward in the early hours after completing one of these “Dragon Tears,” it leads you to a room where a full carved map tells you the location of every single Dragon Tear in the main map, as well as giving you the specific order to experience their tale in a more linear fashion.

Of course, you can do anything in whatever order you want, providing the possibility of getting these tears out of order just by naturally exploring, which can lead you to experience a bulk of this story out of order. That is the nature of Nintendo playing both sides for offering more of a straight line compared to the last game while still giving you total freedom to do and find things as you choose.

Even with the slight inconvenience, the story told here feels more vital than the last one. With the ease of how you can find it, it’s definitely worth doing. Some of the reveals and story moments are some of the coolest in the franchise’s history (ESPECIALLY once you complete them). While just following a mainline path can still give more of a story than the last time, combining that with the Dragon Tears quest definitely provides a richer tapestry than what the last game delivered, and it adds extra weight to the game’s final sequence, which is, by far, the strongest ending in franchise history.

Gotta Ultrahand It To You

Having Link lose his right arm to the Gloom at the beginning of the story, Tears of the Kingdom uses this narrative conceit to provide Link a new arm, in turn giving him a new set of tools for his new journey. The previous tools from the last game are all gone. With his new arm, Link’s replaced abilities include Ultrahand (a better magnet from the last game), Fuse (the ability that lets you mix and match almost everything to an effective and comical degree), Ascend (an ability that lets you ascend through almost every conceivable geometry above you) and Recall (a rewind ability with shockingly unlimited use for some wild puzzle solutions and gameplay moments).

While the set of tools from the last game did give Link some sense of control from the jump that helped manipulate the world to a certain degree, the new set of abilities in Tears of the Kingdom finds Nintendo clearly leaning more toward the physics-based immersive sim sandbox that was hinted at with the last game. It pushes the level of interactivity to a certain level, and it honestly shocks me that it holds together at all without breaking. While it takes some time to get used to, once you understand the nuance of the Ultrahand system, if you have any modicum of creativity, you will be shocked how much the game allows you to manipulate the world in a way that seems impossible, and it just works. And if you are missing any of the abilities from the last game, Tears of the Kingdom has made them inherent to the items you discover now, so you get the best of both worlds.

Through many times in my almost 130 hours of playtime, I spent hours using my own ingenuity to see if there was a way I could try a different solution than the sometimes easily laid out one in front of me, and I was always left with a grin on my face as I saw my crazy solutions work 99.9% of the time. Nintendo put in even more effort than the last game at curating the play spaces in a logical way for people to still succeed at solving things if they don’t feel that creative. Even then, the tools they have given you can still bypass said curation.

In other games, this would utterly break them. In this game, it’s an actual feature and feels congruent to the game, not to mention how the Ultrahand tool has been the source of all the wild creations you have probably seen all over the internet (mechs, lawn mowers, the freaking Metal Gear REX, to name a few). The amount of quality assurance this game needed for all of these elements to hit that perfect sweet spot breaks my mind, and I’m left wondering how in the world Nintendo so seamlessly added things that would only work in more barren, jankier releases with less things going on for them. It is a feat in game design.

Fusion Frenzy

While maybe not as flashy as the Ultrahand ability, Ascend, and Recall, I’m singling out the Fuse mechanic as it single-handedly made the gameplay loop click for me way more than the last game. On top of pairing with the Ultrahand ability for the wild creations at hand, it’s what it does to the moment to moment gameplay that is most important. Weapon durability was one of the bigger albatrosses of the last game for me, with some justifying it as part of the game’s design to encourage more exploration in order to find weapons that replace those that broke. The weapons in the last game felt too fragile to the point that I would actively try to avoid combat as much as I could. A single skirmish could potentially make me churn through weapons way too often, and searching for newer, stronger ones became harder and more annoying the farther I got. The same annoying system from the last game is still present, and weapons by themselves can still break with reckless abandon.

So why does it not annoy me this time around? Because of Fuse.

If anything you find seems like it’s an object you can interact with, 99.9% of the time it means you can fuse that thing to either your melee weapon or your shield, which extends durability for your gear, making it feel less like it was made of fragile glass. When you fuse two weapons into one, the thing that’s fused at the tip of your weapon is the one that breaks first, and you can fuse something else to give your weapon a few more swings before it fully breaks.

The longevity Fuse has added to weapon durability is enough where I don’t walk away from a fight as often as I did the last time, because now there’s a means to not churn away weapons and psychologically stump you from engaging with the game. The fact that you can find a freaking minecart, fuse it to your shield, and then use it as a way to skate for long periods of time is just an example of how wild Fuse is as a mechanic and how interactive and vital it makes everything around you in the world.

The fuse mechanic also brings to light another important element: it makes the loop of collecting every single item you find feel vital now. Just loading back my save from Breath of the Wild, it’s insane how many items you can hoard from so many pickups, and the only real use you had was selling them, using them for cooking, or to upgrade your clothes. Those three elements are still present in this one, but with Fuse, everything you pick can be used with your weapons and even your arrows.

What this means is that, unlike the last game, you can’t find or buy elemental and explosive weapons/arrows in the world as the material you get for Fuse is what will give you the exact same results. For the arrow shooting, it’s the only element that feels like a tiny step back from the last game since it means you have to get the extra step of fusing the element to the arrow (which, to be fair, is a quick button press) every time you shoot one instead of having a set of arrows you can shoot back to back. But it’s a tradeoff I’m willing to take as it has actually pushed me to really fully explore and defeat enemies for them to drop materials to fuse weapons into stronger versions of themselves on the go.

Dungeons and Dragons

A The Legend of Zelda tradition sets the bulk of an entry’s playtime in very elaborate dungeons that test a player’s might and intelligence and rewards them with a tool they use to defeat a dungeon boss that could potentially also be used for better interactions with the world afterwards. From A Link to the Past all the way to Skyward Sword, even with every game introducing its own gameplay quirk, this element was always in play. Breath of the Wild did away with that traditional element in both good and bad ways. For one, it led to the creation of hundreds of tiny, dungeon-like spaces called “Shrines” that were more quick bite in nature, and then the main dungeons (the “Divine Beasts”) lacked a lot of the creativity at display in the shrines. And those Divine Beast dungeons were all so similar looking, they did not make an impression.

Tears of the Kingdom, for sure, tries to rectify this issue. While the shrines are back for this game, the main centerpiece that you visit in the four returning corners of the world are actual temples again, and they at least all look different from each other. While these dungeons still have the same objective as the Divine Beasts, where the main thing is unlocking four to five different locks to reach the main boss, this time it requires a bit more ingenuity from the player than just shifting a floor like what happened with the Divine Beasts. And they fit the theme of the dungeon well.

If I’m perfectly honest, the main thing about dungeons in the older games was getting a boss key to get to the final boss, so this is just a play in the concept and works so much better here than the last game. And some of the boss battles (in particular the Wind Temple one, Colgera) may not be as harshly difficult as the Calamity Ganon variants of the last game, but they sure look different enough to be more memorable boss fights, with some having a level of epicness to them that had me grinning at the spectacle on display.

While, overall, I wouldn’t call all the dungeons here a series best (two of them, the Rito and Gerudo temples could potentially be in that conversation), it is the genuine attempt at bringing back a primary element of the older games, which the last one downplayed, that’s highly appreciated. They feel purposefully built, and the fact that completing them genuinely gives you some great, more frequently used tools to take into the world makes the entirety of the game feel even more cohesively designed than before.

Highway to Hell

The beauty of the abilities/tools given to you with the completion of dungeons is the fact that it improves how you travel through the world of Hyrule this time around. While the first time you enter Hyrule definitely has an air of familiarity to it that, on first impression, may seem underwhelming since it feels so oddly similar, the more you explore it and see what the Upheaval did to this world, the more you begin to appreciate the ways Nintendo freshened up a very familiar looking map (if you have ever played the Yakuza games or a recent game like God of War Ragnarok updating familiar places to a new game, you have an idea of what Nintendo did here). Where the real meat of the world comes from is not only in the ways Nintendo updated the main map, but how it synergizes with the new islands in the sky and the MASSIVE hellscape that is the bottom area, called the Depths.

While the sky islands are more spread out and synergize well with the tower mechanic of this game that both unlocks the area’s map and shoots you to the sky (in a way more fully realizing Nintendo’s initial ideas from Skyward Sword), the underground map of the Depths is quite the sight to behold. The original Breath of the Wild map was already one of the biggest open worlds ever made, and adding both the sky element and the Depths, which is a map that is the literal size of Hyrule, achieves a grand level of scale for Tears of the Kingdom. It is remarkable that the game is able to render it all almost without any loading. The fact that the adventure can so seamlessly take you from the sky, to the main land, and into the Depths, all while maintaining an incredible sense of grandeur since almost everything you see in the distance is somewhere you can go, feels like an act of technological black magic.

And the design of the Depths is no slouch, either. The environmental density of the place is definitely grand and different from the main Hyrule map, and its initial pitch black nature, which requires you to find the seeds at the bottom which coincidentally coincide with the shrines from the main map, adds an extra level of thoughtful synergy to your adventure. Being in the Depths can sometimes be terrifying in nature. The enemies here hit you way harder than the variants in the main map. The Gloom here can neuter your health, making you more thoughtful on the way you engage with every element in this map. Some of the creatures you face here have a terrifying feel to them in the darkness of the world that you don’t feel in other places.

The fact that some of the greatest rewards (including some of the outfits lifted from older Zelda titles, as well as tools to help you build the crazy creations) are here means that there is always a big reason to really engage in this massive new map that’s always beneath your feet. The amount of hours I spent scrounging and uncovering this map provided me the greatest thrills, especially facing one of the game’s toughest bosses that made this feel as close to a From Software game as the Zelda franchise has ever felt.

A Technological Marvel

This bears repeating: the fact that this game is running on the Nintendo Switch at all, knowing its ambition and the incredibly limited hardware within it, is a technological marvel. When the last game came out in 2017, it definitely felt like it potentially had already maxed out the system with a game quite impressive for its size. Tears of the Kingdom triples the size of the last game to the point where it feels more ambitious in scale than even games released for the more powerful current generation of consoles. The fact that it deals with a level of physics manipulation that could literally make games combust and crash down in real time I reckon will be something many developers study in the years to come.

Does the game have problems? Absolutely. Even though it manages to run smoother than the last game in many comparable areas, using things like Ultrahand will sometimes lead to some framerate dips, and only during times where you abuse particle effects on screen does it feel like the game can’t keep up with what’s onscreen for a brief moment. Yet those moments are so rare, and the game, even at 30fps, is framepaced so smoothly that you will immediately forget about any framerate issues for literally the bulk of your playtime due to how polished everything else is.

And while the low resolution and bland texture here and there can sometimes spoil the look, the game’s cel shaded art style still pulls its weight to provide beautiful moments, even when you know it’s coming from a severely underpowered machine. When I’m skydiving while the sun is setting, and I look at the horizon to see the massive environment and islands in the distance and think how those are all places that I can visit, all while looking picturesque, it creates beauty even from such a squeezed-out rock.

The Stuff of Legends

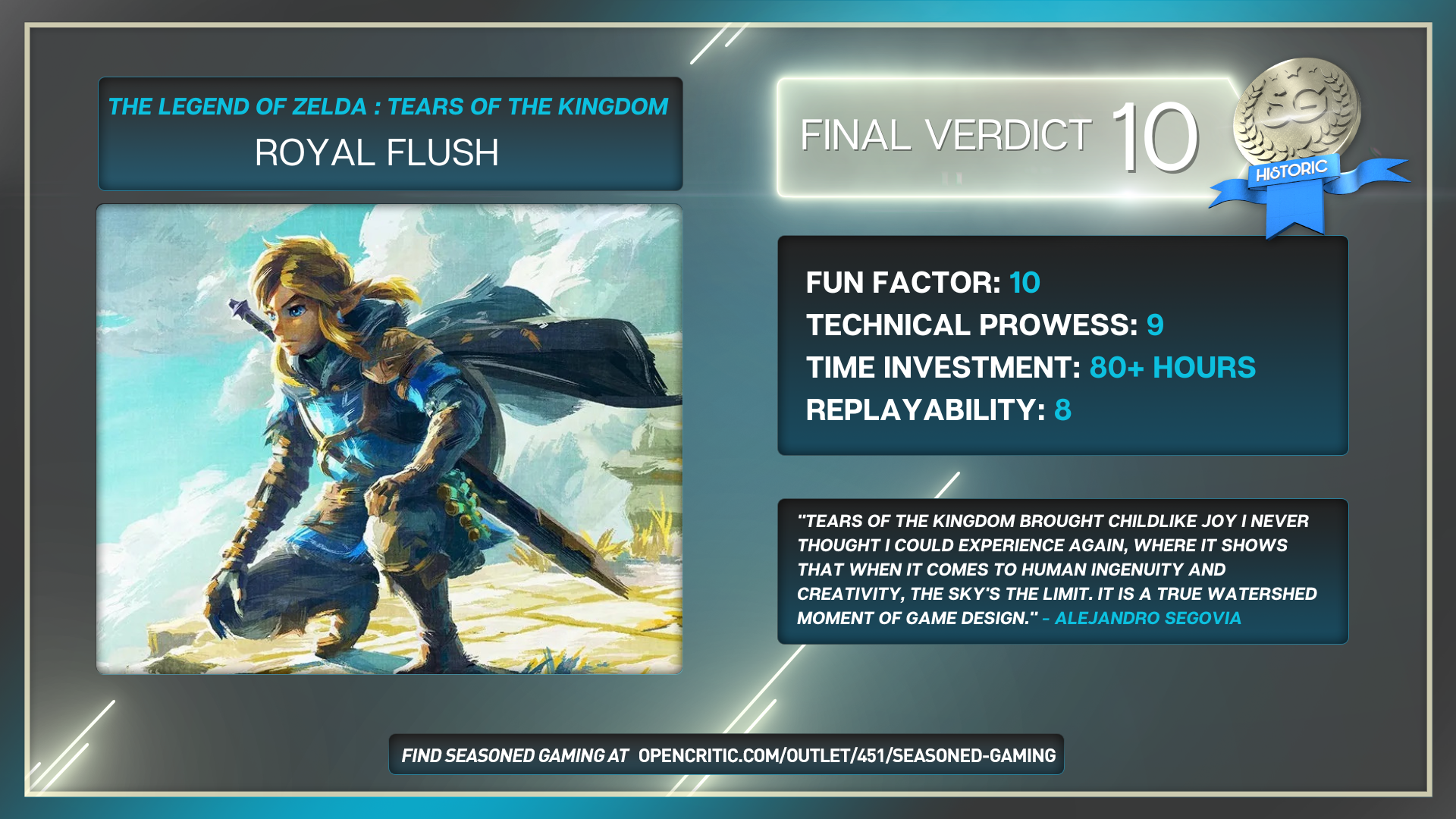

There is so much stuff to talk about, still, that I feel there is no need to further drive the point about what a monumental achievement The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom is. As someone that respected the great parts of Breath of the Wild while also scoffing at its unanimous praise, coming into this one, I didn’t expect I would walk away from this with what may be my all time favorite entry of this franchise (an honor I’ve always reserved for The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker in my heart).

I always knew Breath of the Wild could be even more than what it was, and I’m glad Nintendo proved my instinct right and gave me almost everything that was missing from the last entry and more. Even after 130 hours, I want to play more, complete even more sidequests and learn more about the fleshed out population, scrounge every last iota of the hellish Depths and its secrets, and defeat every monstrous Gleeok. And with the creativity on display, I can’t wait to even attempt to build all of the insane creations I see online that break my mind they are even possible.

The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom brought childlike joy I never thought I could experience again, where it shows that when it comes to human ingenuity and creativity, the sky’s the limit. It is a true watershed moment of game design.

You can find Seasoned Gaming’s review policy here

[…] manner that you changed all gaming focus to that game? Titles like Diablo IV, Street Fighter 6, and The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom have caused many a sleepless night, but most of us understood that those nights were coming. We […]